Naming the Animals

CURIOUS MATTER, April 3 – May 15, 2011

PROTEUS GOWANUS, April 16 – July 17, 2011

Naming The Animals was a special collaboration between Curious Matter in Jersey City and Proteus Gowanus in Brooklyn. The two-part exhibition ran concurrently at both locations and was a complement to the yearlong inquiry hosted by Proteus Gowanus on the theme of Paradise.

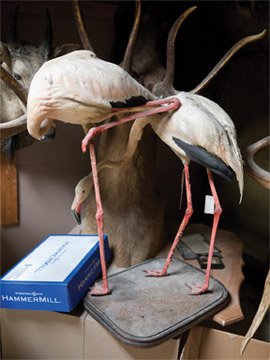

Joanna Ebenstein, Natural history museum storage area, 2010. Giclee print, 11 x 14 inches.

Heather Layton, Saving the Goats, 2010. Tea and watercolor on paper, 18 x 24 inches.

Colette Male, Sailors’ ivory carvings c. 1560. Found South Pacific, 1850. Figure 3, 2011. Shell, coral, wood, plaster, plastic, resin, paint, wax, 4 1/3 x 3 1/2 inches.

IN OUR COLLECTIVE EFFORT to understand the world, we’re driven to name and catalog everything around us. From the detailed observations of prehistoric cave painters through modern ecology and zoology, humans have been compelled to describe and render the other living things that inhabit the earth. Not necessarily purely aesthetic or scientific, naming and cataloging can include the assignment of moral or metaphorical associations. Implicit in these actions is our desire to declare and understand ourselves.

The ancient Hebrews and the Christians who adopted the Old Testament believed that God gave Adam the task to name all the animals in Paradise. Each creature was brought before Adam and he decided what they were to be called. Giving names to things outside of ourselves was a vital step towards our humanization. The process transformed something tangible into an abstract idea. And so, with abstract ideas, communication became easier. A name allowed others to grasp what was being referred to without its physical presence.

Aristotle is the earliest natural historian whose work has survived. His History of Animals (c. 350 BC) is considered the pioneering work of zoology and has influenced both religious and scientific thought for centuries. Around the 2nd century AD, the Physiologus was compiled. This is a collection of writings on animals, much of which seems to have come from Aristotle’s History of Animals (also Pliny the Elder, Herodotus and other ancient sources), but adds allegorical stories that have a Christian message. These manuscripts were lavishly illustrated and through repeated copying and addendums, evolved into the Medieval Bestiaries.

It is the medieval interest and collection of holy relics that spawned the development of Cabinets of Curiosities. These cabinets were popular through the Renaissance to the 19th century, and their appeal is perpetually rediscovered. These collections were an attempt for the collector to have knowledge of all of God’s creation on Earth, thus they acted as a theatre of the world and if they included ancient artifacts, they took on the concept of a Memory Theater.

In our exhibition, Naming the Animals, contemporary artists explore the human impulse to describe and classify the world around us. Much of what was illustrated in medieval bestiaries were creatures from various mythological cultures. Inna Razumova shows us just what kinds of creatures the human mind can conceive with her piece, Hybrid Data Set 3: Satyroid, Sea-Demon, Manticore Tatary, Manticore. Florence McEwin and Colette Male both explore the folklore behind the beasts in their work. McEwin takes on the more familiar dangers of the wolf and werewolf legends in Tango. Here we have a real creature whose dangers are known, but around which has grown a corpus of legend that aims to keep humans away from any interactions in the interest of safety. Male on the other hand takes on the notion of the corruption of a remembered sight, or perhaps the exaggeration of what was seen to extract added admiration from the listener. Her Sailors’ Ivory Carvings c. 1560. Found South Pacific, 1850. Figure 3 and Figure 4 are examples of just such imagined fish stories from sailors. Katherine McLeod has a different take. Her Tear Shaped Like a Bad Engagement Ring shows what can result from only hearing a description of an animal. It brings to mind Durer’s interpretation of a rhinoceros in his famous print where he tried to flesh out an animal he had not himself seen.

Cabinets of Curiosities had their heyday during the Renaissance and Hans van Meeuwen’s Oor would have fit into any collection. His depiction of a gigantic deer’s ear takes on iconic and abstract elements at once. At first we’re seduced by its shape, without necessarily understanding what it depicts. Eventually the association hits us and we can place the form to the absent animal. Suzanne Norris with 13 Wonders from a Cabinet of Curiosities has updated the traditional laborious illustration of the objects in a cabinet. Her pared down drawings capture the submersion and suspension of the silently floating relics within their fluid filled jars.

The 19th century brought forth industrialization and its concurrent development of leisure time. This, along with an England on whose empire the sun never set, found Europeans in places they deemed exotic and brought forth a renewed interest in the flora and fauna of the world. The Victorian naturalist’s penchant for collecting specimens from far corners of the globe resulted in some remarkable examples of taxidermy. Lasse Antonsen has resurrected the 19th century sprit of the taxidermy mount in Vignette. While Joanna Ebenstein, goes behind the scene into the vaults to unearth an original antique mount and give it new life.

The modern view of natural history is to do as little harm to the environment and the animals as possible. Eric Lindveit’s hyper real recreations of tree trunks follow this philosophy. Sylvan Natural History of New York #2 is such an accurate depiction of tree bark with a fungus growth that it is difficult to resist testing their truth by touching. Tricia Zimic records just those ecological issues that have become prevalent in today’s polluted and over built environment. With Adaptation (Blue Spotted Salamander) we see a discarded can amid the forest floor litter; testament and symbol to our disregard for the habitats of our fellow creatures.

Beyond the natural and into the future, Julia Barnes takes on the emerging science of bioengineering. With Orchid–Bat (Wispy) she imagines the outcome of the gene splicing of a bat and an orchid. The horrible beauty of the outcome is transfixing in its repulsion. And so full circle from Manticore to Sasquatch; from allegorical imaginings to cryptozoology, Jennie Suddick takes us into Bigfoot family life with her piece Commune II.

The diversity of life is reflected in the diverse interpretations of these artists. Each has gone on their own expeditions of the imagination and observation of the natural world. They have transposed and combined those ideas into the works presented here. We share the earth with a variety of life forms and as the curious ape that has taken on a divine task; we give an identity to all that we see.

—Curious Matter

Welcome to Paradise: a collaboration

Every September at Proteus Gowanus, a nine-month investigation is launched, using art, artifacts, books, workshops and performance in pursuit of a single theme. Multiple avenues are traversed in an interdisciplinary search for understanding and inspiration. This year’s theme, Paradise, has been examined in two exhibitions and through numerous events, using multiple media as tools: paint, video, clay, diagrams, maps, poetry, soup, sermons and song. As we were planning the third and final chapter of Paradise, our friends at Curious Matter proposed a collaboration: they would install an exhibit within our exhibit which would focus on a most curious event that took place within the walls of Paradise: the naming of the animals.

Myth says that naming the animals is an obligation assigned to humankind at the creation and it is one that has never ceased to demand attention: the task of naming, ordering, cataloging, dividing, pairing, discerning, describing, speaking…. Indeed, Paradise itself, where naming first began, was a place divided and separated, which is why its beatific presence bedevils us. As the exhibitions at Proteus Gowanus and Curious Matter attest, these paradisiacal topics have a light and a dark side.

By mid-July, when the Proteus Paradise year comes to an end, more than 100 artists, designers, cartographers, writers, tour guides, architects, cyborgs, medievalists, musicians, filmmakers and gardeners will have contributed to this investigation. And what have we learned so far? Essentially aspirational (whether toward the future or the past), Paradise is built upon a foundation of loss and, in our explorations, howling mouths, grasping monkeys, fathomless depths, endless searching, absolute termination and the Devil himself, have vied for place alongside green gardens, quiet still lives, nostalgic dreaming, all-knowing technologies and sustainable urban utopias.

Proteus Gowanus seeks to create an alternative, culturally rich environment designed to stimulate the creative process; a place where the boundaries between the artist and non-artist fade, where images and ideas from disparate disciplines are juxtaposed to create new meanings. We are thrilled to be joined in this endeavor by the fine-tuned sensibility of Curious Matter and welcome the opportunity to harness Jersey City to the Gowanus in the never-ending search for Paradise.

—Proteus Gowanus

THE ARTISTS

Curious Matter

Lasse Antonsen

Julia Whitney Barnes

Jill Marleah Bell

John Bell

Arthur Bruso

Travis Childers

Matthew Cox

Joanna Ebenstein

Veronica Frenning

Patti Jordan

Heather Layton

Ross Bennett Lewis

Carrie Lincourt

Eric Lindveit

Colette Male

Marianne McCarthy

Florence Alfano McEwin

Hans van Meeuwen

Raymond E. Mingst

Elizabeth Misitano

R. Wayne Parsons

Inna Razumova

Debra Regh

Andrew Cornell Robinson

Proteus Gowanus

Kristi Arnold

William Brovelli

Christian Brown

Ryan Browning

Travis Childers

Clair Chinnery

Eileen Ferara

Richard Haymes

Ellie Irons

Katherine McLeod

Suzanne Norris

Melissa Stern

Jennie Suddick

Tricia Zimic