Dangerous Toys

October 13 to November 11, 2012

THE ARTISTS

Aaron Beebe

Zoe Bellot

Arthur Bruso

Sasha Chavchavadze

Anthony Heinz May

Raymond E. Mingst

Heather Molin

Douglas Newton

Neal Anthony Pitak

Debra Regh

Margaret Roleke

Lance Rutledge

GUEST CURATOR

Sasha Chavchavadze

Anthony Heinz May, Game of Stick, 2011, Wood, paint, 40 X 20 X 4 inches.

Zoe Bellot, Bird, 2010, Mixed media, 13 X 17 X 7.25 inches.

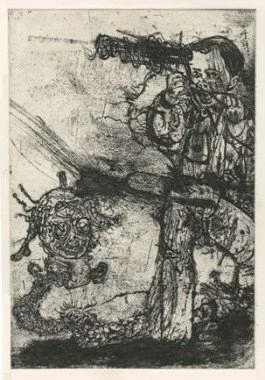

Neal Anthony Pitak, Hand Games, Intaglio, 16 X 24 inches.

Lance Rutledge, Shiva Eye, 2012, Ink on paper, mounted on board, doll part, 7.25 X 3.75 inches.

Introduction

Step on a crack, break your mother’s back.

Step on a nail, put your father in jail.

Step in a hole, break your mother’s sugar bowl.

Step on a line, you break your mother’s spine.

Step in a ditch, your mother’s nose will itch.

–Children’s Rhymes

WE FIRST MET SASHA CHAVCHAVADZE through her role as Founding Director of Proteus Gowanus in Brooklyn, New York, a “multi-disciplinary gallery, project space and reading room.” We’d been attending lectures and exhibitions hosted by some of their projects-in-residence and resonated to the themes. The space is a constant hive of activity and the passionate sense of creative exploration drew us in again and again. As we met more of the partners involved in particular initiatives we also discovered Ms. Chavchavadze’s own body of work as an artist.

Inspired in part by a game invented by her father, Ms. Chavchavadze “explores the Cold War, its antecedents and its legacy through visual art, documents, photographs, books, memorabilia, and publications.” Museum of Matches is her fascinating, multidisciplinary art project and it includes the book by the same name. At the start of Museum of Matches she quotes an email from her father, David Chavchavadze, “The match game was invented by me in 1940. In those days there were kitchen matches that could be lit by almost anything…. The matches represented individual soldiers and had insignia of rank. The game was played outdoors and the matches were stuck upright in the sand or dirt representing trenches or foxholes. If it was my turn I fired a BB gun at the enemy’s matches…. Matches that were knocked down were wounded and given a stripe. If a match was lit it was dead.”

The match game has served as a metaphor that courses through Ms. Chavchavadze’s artistic inquiry. We’ve been captivated by the lively interplay of media that has produced such a multi-faceted body of work and the use of matches as both game piece and artistic medium. The lurking aspect of danger within her work provoked us to ask for her perspective by curating Dangerous Toys. We were certain Ms. Chavchavadze would bring a compelling point of view and she has managed to surpass our expectations. She has presented us with an expressive and appropriately unsettling exhibition. The keenly focused collection is in turns beautiful, playful and startling.

We’re honored to have had Sasha Chavchavadze shape Dangerous Toys and thank her for much beyond this production. Thanks to the participating artists as well, without whom the show would not be possible, and to our audience who have been invigorating players in each Curious Matter project.

RAYMOND E. MINGST | ARTHUR BRUSO

co-founders, Curious Matter

Playing With Matches

I’VE BEEN PLAYING WITH MATCHES FOR YEARS. I make assemblages of multi-colored matches that I display with historical documents and photographs in a “one-room Cold War museum” called the Museum of Matches. When I work with matches I feel a sense of danger and risk, but also the imaginative excitement of a child playing with a toy. The imminent possibility of both creation and destruction is always at hand.

I take no risks with my matches, carefully painting the tips with acrylic paint and sealing them under Plexiglass. Recently, I invited an artist to contribute an exquisite sphere of multi-colored matches to my museum, fabricated with old dual-tone pre-safety matches ordered on Ebay. Weeks later, the beautiful, will o’ the wisp (translated from Latin as “foolish fire”) rolled along a wall and self-ignited, setting off an enormous explosion of flame that engulfed my museum. The experience, though traumatic, was strangely freeing.

There’s a lot of focus on “safe toys” for children these days. Rubber mats are placed under jungle gyms. Warning labels abound. We are a “no risk” society, keeping death and destruction always at bay. Yet, in order to achieve this, we make weapons as available as toys, and we guard our shores with a nuclear arsenal that could destroy worlds.

Ironically, the things that should be “dangerous” in our culture because they can effect the most dramatic change, are also reduced to toys. The most revolutionary art looks like a play thing when hung in our mega-museums, as if its power had been leached out of it. Perhaps today the term “dangerous toys” could be a euphemism for art that inspires, that has meaning, that challenges?

Debra Regh and Raymond E. Mingst’s “games” suggest the danger and real risk that underlies our culture of “safety.” Neal Anthony Pitak’s intaglio prints are a perfect medium to express the violence behind children’s “war games.” Heather Molin’s sketches describe teenagers stupefied in front of a computer and television, a ubiquitous contemporary “toy.” Douglas Newton’s “mood scape” of toy airplanes expresses our culture’s underpinnings of danger. Zoe Bellot’s music box, playing “How Sweet it is,” evokes the melancholy and fear behind our obsession with entertainment. Margaret Roleke’s amorphous pink forms comprised of toy soldiers navigate the line between beauty and danger. Anthony Heinz May’s toys and games, “rearrangements of nature,” grapple with the dangerous impasse between nature and technology. Arthur Bruso’s humorous “lions” describe the primal fear stretching back millennia, expressed in our best children’s toys. Aaron Beebe’s ode to the artist Sigrid Sarda suggests that her disquieting sculptures are “dangerous toys” that challenge, disturb, and effect change. Lance Rutledge’s all-seeing doll’s eye gazes upon the debacle like a Hindu god of destruction.

SASHA CHAVCHAVADZE, Curator

1) Museum of Matches by Sasha Chavchavadze,

published by Proteotypes, 116 pages, ISBN 978-0-9827234-2-5