A Time in Arcadia

May 19 — June 23, 2013

Presented by Curious Matter & The Jersey City Free Public Library – a special collaboration featuring work by 33 contemporary artists and a bibliography of nearly 200 selections from the Main Library’s 6 Departments and 9 Branches.

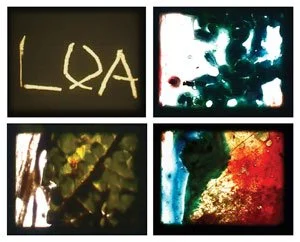

Ewelina Bochenska, (film stills) LOA, 2013, 16mm film decayed in homemade concoctions, including tumeric, fruits, flowers and organic material. 5:39 minutes.

Vikki Michalios, Soilless and Sunless, 2013. Glass, LED grow lights, rockwool, bean stalks, 12 inches square, variable height.

Sabina Magnus, Tastes Like Chicken 4, January 2013, Stoneware, glaze, 3.25 X 10 inches.

Richard Lapham, Black Square, 2012, Silver gelatin print, 8 X 10 inches.

“Is not thilke the mery moneth of May,

When loue lads masken in fresh aray?

How falles it then, we no merrier bene,

Ylike as others, girt in gawdy greene?

Our bloncket liueryes bene all to sadde,

For thilke same season, when all is ycladd

With pleasaunce: the grownd with grasse, the Wods

With greene leaues, the bushes with bloosming Buds.

Yougthes folke now flocken in euery where,

To gather may bus-kets and smelling brere:

And home they hasten the postes to dight,

And all the Kirke pillours eare day light,

With Hawthorne buds, and swete Eglantine,

And girlonds of roses and Sopps in wine.

Such merimake holy Saints doth queme,

But we here sytten as drownd in a dreme.”Edmond Spencer

A Sheperd’s Calendar, 1579

WE DREAM of Arcadia. Whether it’s called Eden or Shangri-la, we long for a verdant and fecund place where food comes without toil and peace fills our days. Some cultures have taken a more proactive approach to attaining this dream and set aside land to build their own Arcadias. Persian paradise gardens and the Italian Renaissance Mannerist gardens were attempts, by those with the means, to create a place separate from the dreary drudgeries of life. Extravagant fountains and statuary complemented clipped hedges and trellised vines, all surrounded by a wall to protect the sanctuary.

Not all gardens were so grand and ornamental. Medieval monastery gardens could be intimate in scale and cultivated solely for food and medicinals. The plants themselves being the most vital component. For most life on Earth, plants are the base of the food chain. Their importance is nearly absolute. Relying upon the plentiful light of the sun for survival, plants create their own food. Often they produce more than they need at any one time. These stored reserves feed the rest of life on Earth. Roots, stems, leaves, seeds and fruit are all exploited by the diversity of living things to obtain their own nourishment for survival.

Aside from the practical uses of plants, there is the aesthetic appeal. Humans appreciate the prospect of a landscape and the scent and hue of a flower. We feel refreshment in the mere depiction of the dappled shade of a copse in a work of art. We long for a verdant oasis, so we paint one. The Bronze Age (1500 BC) Minoans were among the first cultures to depict pure landscape in art, without humans or animals. The ancient Greeks and Romans painted many landscapes, sometimes to lend interiors the illusion of an infinite vista. In Medieval art, the landscape was relegated to the background of paintings. It took the Dutch in the 1600s to again elevate pure landscape painting to importance. However, the representation of plants as decorative motifs and in herbals has been widespread through the ages.

With our latest exhibition, A Time in Arcadia, Curious Matter gathers inspiration from our botanical world. From Paradise to Monsanto, the artists assembled here have responded to the syrinx of Pan in the Arcadian hills.

Marianne McCarthy’s “Hianeechee Ghuni: The Tree that Walks by Night,” in the Gothic mood of nineteenth century Romanticism, depicts the forest as the place of primeval horror, where death awaits in its ever present gloom. Gilda Pervin with “Wired 3” and Robert Mullenix’s “Disclosure” also expose our fear of the dark and dangerous forest. Or, perhaps they’ve simply brought us to a place of reprieve from the glare of the sun?

With a nod to the ancient herbals and present day botanical studies, Aaron Beebe’s “Untitled (Absorption)” submits the scientific paper as the work of art. Vikki Michalios, with “Soilless and Sunless,” finds inspiration in the laboratory practice of agricultural study.

The Victorians in the 1800s developed a passion for all things botanical, from the development of vernacular gardening, to the pressing and preserving of plant specimens. Expeditions to remote and dangerous locales to discover new plants were funded by governments and museums. Lasse Antonsen’s “Magic Lantern Botany” series considers the Victorian preoccupation with the exotic.

Among the many practical plant uses is the production of dyes and pigments. Kit Lagreze paints her “Engross” with the pigments derived from dahlia flowers and tea. While Sabrina Magnus projects the development of new plant-based hybrids into the future with “Tastes Like Chicken.”

Flowers as symbols have been a shorthand to understanding throughout the ages. Debra Regh’s “Dear Friedrich,” contemplates the blue rose as a symbol of rarity and the acme of desire. Joan Mellon allows pthalo green to stand in for the color of the entire vegetal kingdom.

Both Corinne Schultz’ “Entanglement” and Robert Schatz’ “Salix” see the landscape in terms of its linear qualities, using parts to explain the whole. Richard Lapham finds an order in the landscape that may either be imposed by the hand of the artist or revealed by his vision.

Samantha Persons’ “Acadia Fig. 5” recreates the youthful ideals of her childhood Eden, yet we find our human interventions merely temporary as Stephanie Guillen shows us with “Reconquering Centralia.” Nature always returns the earth back to the Arcadia it was before man’s interference tried to change it.

We depend on the resiliency of nature to heal the wounds we inflict upon it. The Earth so far, has been stronger and smarter than us, as it recovers again and again from our onslaughts and foibles. Most of the artists in A Time In Arcadia see the dark side of our manipulation and exploitation of the plant kingdom for short term and selfish goals. There’s an intimation that we are on the brink of disaster, that Nature will not spring back so easily as in the past. But as Demeter had been coaxed out of her grief and cajoled into relaxing her winter’s grip on the land, so will Persephone return and avert a new disaster before the Earth becomes desert, because the dream of Arcadia is constant.

RAYMOND E. MINGST • ARTHUR BRUSO

co-founders, Curious Matter

.

OPENING RECEPTION:

Sunday, May 19, 2013, 3:00 to 6:00pm

Curious Matter, 272 Fifth Street, Jersey City, NJ 07302

Artworks will be on display at Curious Matter & The Main Library. Selections from the bibliography will be available in every department and each branch of the library.

Curious Matter

272 Fifth Street, Jersey City, NJ 07302

Regular hours: Sundays noon to 3pm and by appointment

The Main Library of the Jersey City Free Public Library

472 Jersey Avenue. Jersey City, NJ 07302

Hours: The Main Library is open Monday to Thursday 9:00 am to 8:00pm; Friday and Saturday 9:00 am to 5:00pm.

more info: [w] www.jclibrary.org [t] 201-547-547-4526

THE ARTISTS

Curious Matter

Lasse Antonsen

Aaron Beebe

Ewelina Bochenska

Arthur Bruso

Robyn Ellenbogen

Stephanie Guillen

Jamie Isaia

Kit Lagreze

Richard Lapham

Ross Bennett Lewis

Joe Lugara

Sabina Magnus

Marianne McCarthy

Julie McHargue

Joan Mellon

Vikki Michalios

Raymond E. Mingst

Robert Mullenix

Samantha Persons

Gilda Pervin

Robert Schatz

Corinne Schulze

Leona Strassberg Steiner

Margaret Withers

The Jersey City Free Public Library

Lasse Antonsen

Kristi Arnold

Jessica Baker

Aileen Bassis

Greg Brickey

Eileen Ferara

Jessie Horning

Richard Lapham

Joe Lugara

Sabina Magnus

Anthony Heinz May

Sarah Pfohl

Debra Regh